2024 was a strange year for me creatively. It was productive, but fragmented, with my attention split between active game development, video production, and a handful of smaller side projects. This recap isn’t intended as a list of achievements, but rather as a reflection on what worked, what didn’t, and what I learned from spreading my attention too thin.

This post is about focus, trade-offs, and learning where my time actually goes.

Three threads defined my year: Something in the Water, the SENTRY Early Access launch, and a short but surprisingly valuable DOOM mapping challenge. Each taught different lessons about scope, momentum, and how I want to approach my work going forward.

Over the last two years I’ve shared year-end wrap-up videos covering the projects I’ve worked on. For 2024, I wanted to continue that tradition whilst adding a little more context and insight. The video below is a high-level snapshot of the year; the sections that follow explain what happened during this time and what I took away from it.

How Devlogs Hurt Momentum on Something in the Water

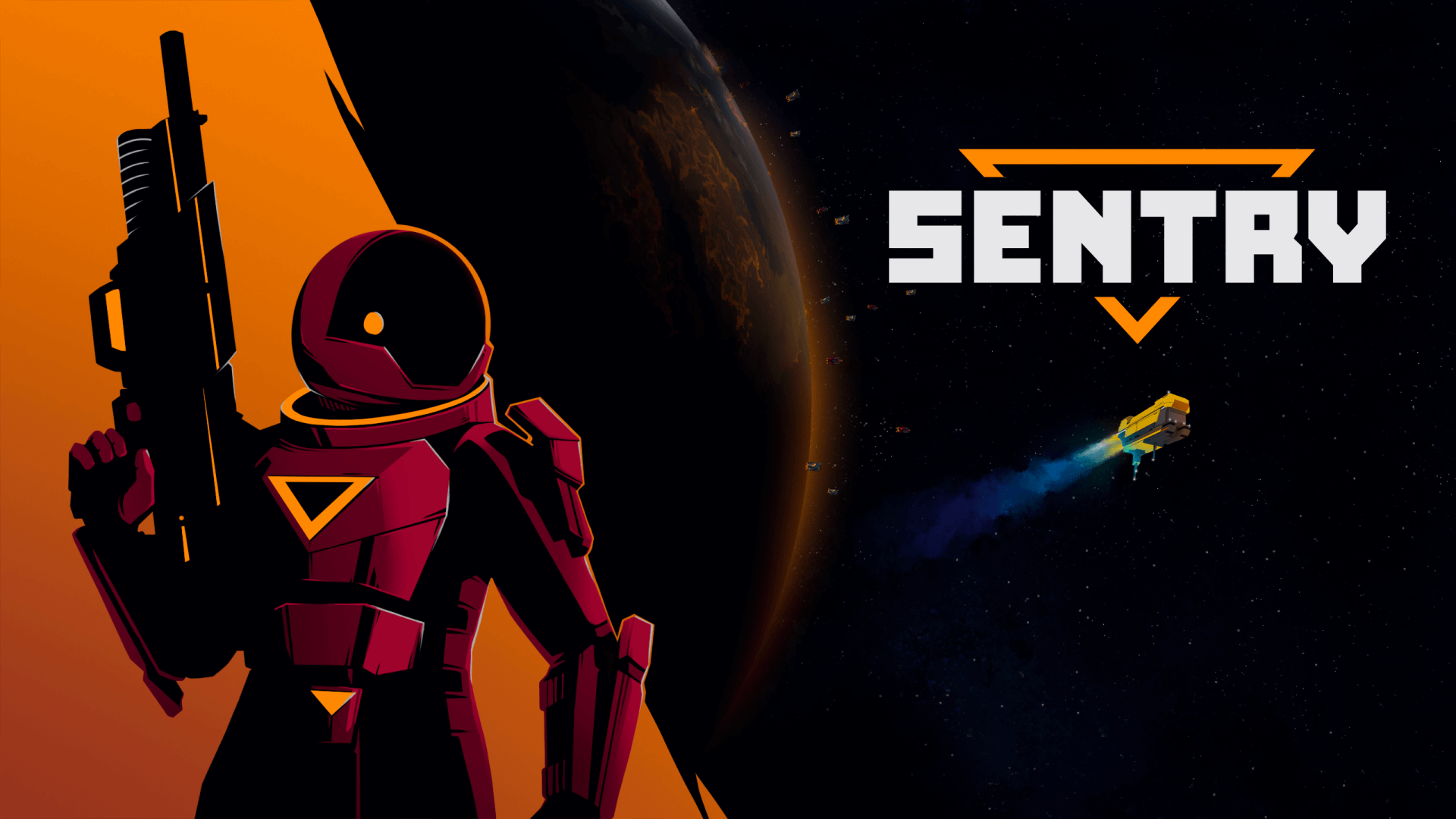

A significant portion of 2024 was spent working on Something in the Water, my retro-leaning solo survival horror project. Progress was steady, but slower than I would have liked. A major reason for this was my decision to document development through devlogs and video content alongside the work itself.

On paper, this made sense. Video devlogs offer visibility (at least initially), accountability, and a long-term record of a project’s evolution. In practice, they came at a significant cost. Planning, recording, editing, and publishing video is a substantial commitment, and the expectation of consistent uploads made the impact worse. Tasks that should have taken an afternoon often stretched into multiple days once video production was factored in.

I initially assumed this would be a one-off cost. The first devlog required defining a format, pitching the project, and finding an editing style. So I expected things to settle down after these steps. What I didn’t account for was how heavy the editing process would remain, the time required to find usable capture footage, or how disruptive frequent context switching would be for solo development.

When I started planning a follow up devlog, I quickly realised there was a problem: the story I wanted to tell didn’t match the state of the game or the footage available. I just couldn’t get things to line up. Continuing would have meant shifting focus away from code tasks like refactoring the interaction system in favour of showing more varied environments or encounters. Even coming up with supplemental material or b-roll was enough to fracture what little momentum I had.

That was the point where I had to confront an uncomfortable truth: video production is its own discipline. Doing it well competes directly with development time, a cost that’s multiplied on a solo project.

Here’s the devlog in question, covering work on Something in the Water over the year.

The lesson here wasn’t “don’t make videos”, but rather that I need to be far more deliberate about when and why I do. It’s always worth remembering:

Documentation should serve the work, not fragment it.

That being said, the response kinda blew me away. At the time of posting, I had around 1000 subscribers – a number that doubled shortly afterwards. I must have been blessed by the algorithm! However, this success created its own pressure, by tempting me to follow up quickly, despite development not being in a good state to be meaningfully captured. There simply weren’t clean narrative milestones to make for a good video. As with every social media-driven dopamine hit, it was very tempting, and I think it skewed my personal perception a little. It’s hard to not want more.

So I held off. I chose not to push out another devlog when the project couldn’t tell a complete story, entertain or educate. Going into 2025, that’s something I’d like to approach differently. I will aim to integrate video production in a way that supports momentum rather than undermining it. Basically, that means continuing to drip-feed progress on social media, but not committing to spend time on a fully edited devlog video unless there’s a clear story to tell.

This experience had a direct impact on how I approached work when switching back to a team environment – which brings me to SENTRY…

What Early Access Feedback Taught Me About Scope and Design

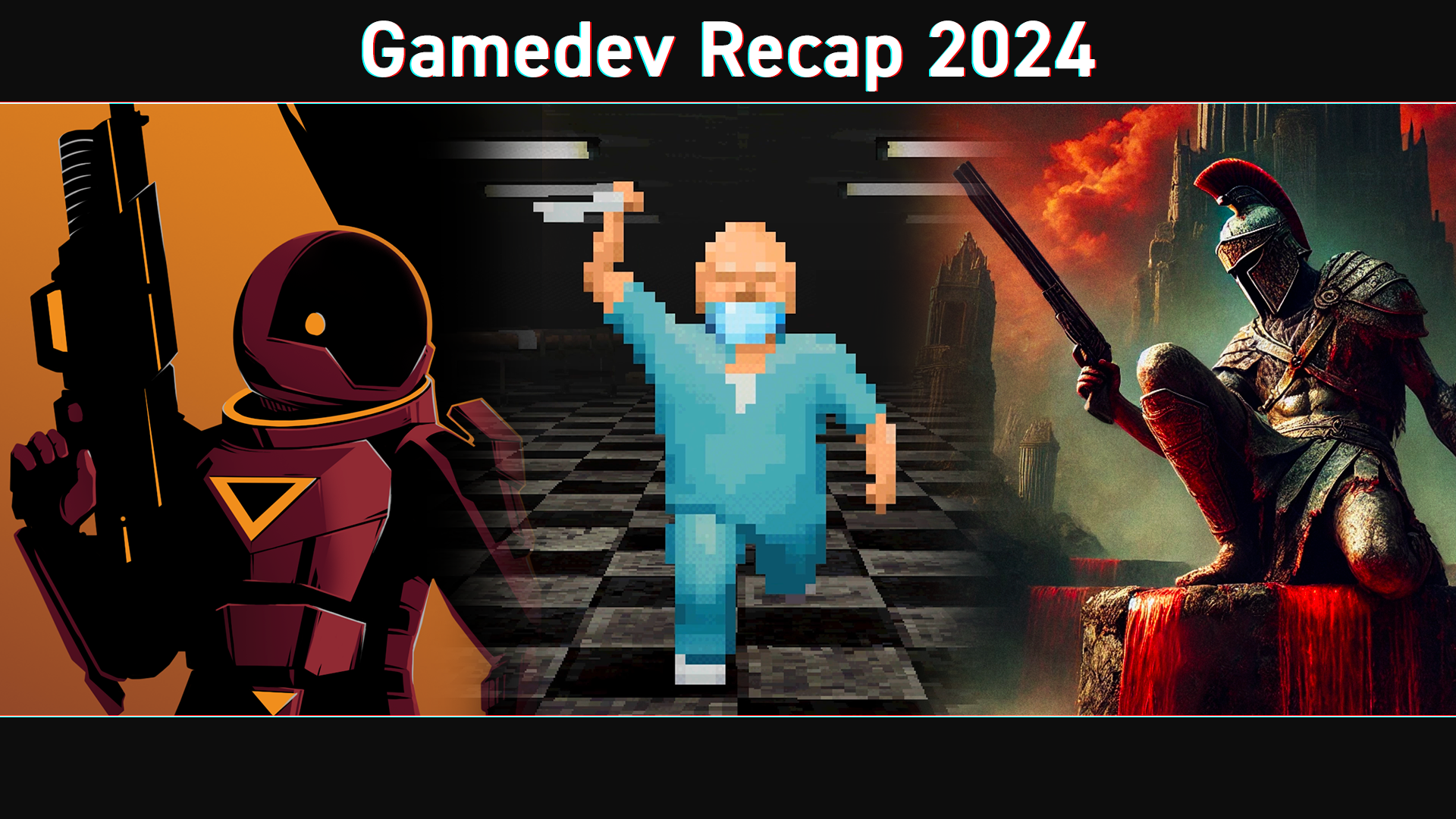

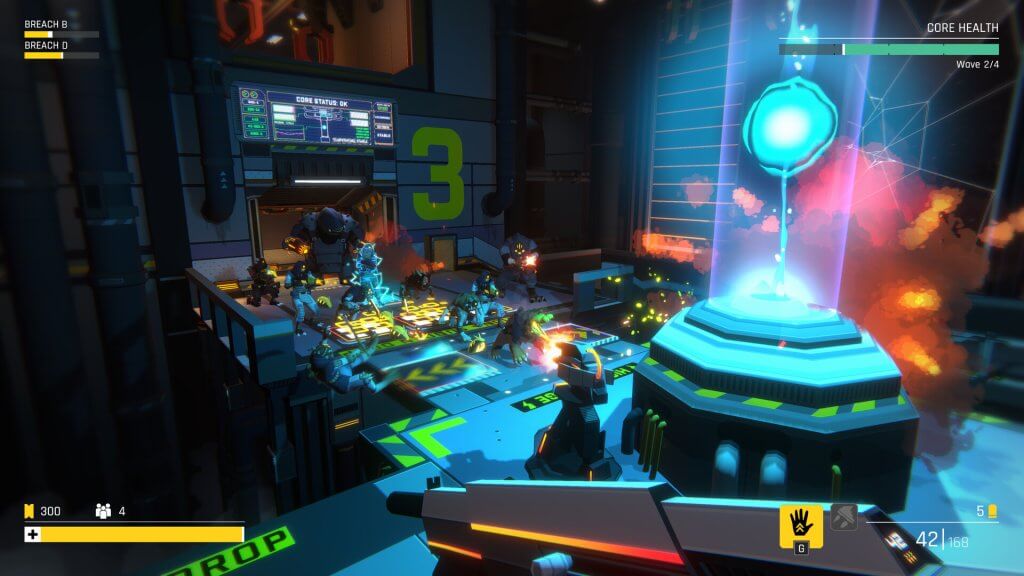

After what is now the longest single production of my career, SENTRY released into Early Access at the end of March. It was the most externally visible milestone of the year, and in many ways, the most instructive.

Launching into Early Access fundamentally changed the nature of development. Design decisions were no longer hypothetical, but instead became direct responses to feedback from real players. That feedback was immediate and concrete, arriving through Steam reviews, forum posts, YouTube videos, Discord conversations, and Twitch streams.

The initial response was mostly positive, and it was a huge relief to finally get the game into player hands. That said, there were aspects of the game that came as a surprise to some players. For example, roguelike elements were not present in the pre-release Steam demo, and had limited coverage in our promotional material. This caused a slight mismatch between player expectations and experience.

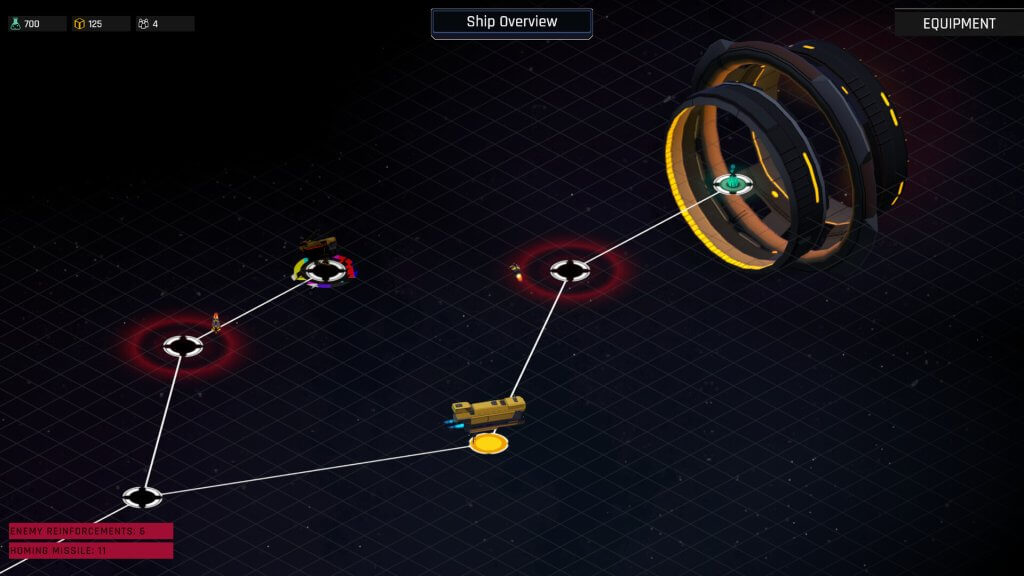

To address that gap and better prepare players, I produced a launch trailer focused specifically on the strategy layer.

Communicating these systems was challenging. Strategy mechanics are often rather dry, and rarely read as “exciting”, so a lot of work went into pacing, clarity, and telling a visual story. I tackled this by showing one action at a time, leading the eye between shots, and building a sense of ceremony around otherwise dry mechanics. That process taught me a lot about how to communicate complex systems quickly and clearly, especially within the constraints of a short trailer.

Early Access feedback also highlighted issues around difficulty and perceived game length. These concerns became the focus of our first major update in the form of June’s Starfarer Update.

Responding to Feedback: The Starfarer Update

One of the most common points of feedback centred on the Long Range Missiles. These launch after a set number of turns and hunt the player down, ending a run on impact. The intention was to create urgency and reinforce the narrative pressure to escape, but many players struggled to abandon their instinct to explore and collect everything, often pushing themselves into unwinnable scenarios.

To address this, we introduced a tiered campaign structure. Players now begin with a shorter, lower-challenge Initiate run before progressing to the tougher Starfarer run. The missile mechanic was reserved for the latter, while Initiate runs instead introduced Stalker ships. These offered a softer, but still meaningful consequence by challenging players with additional (and tougher) enemy boarding parties rather than ending the run outright.

I generally prefer incentive-driven solutions over punitive ones, but in practice “sticks” are often the most economical way to solve a problem quickly – at least while you’re still growing your “carrots”!

This approach aligned better with player behaviour while preserving the underlying design intent. It also reflected a broader shift toward roguelike-style progression: using structure and motivation to guide players, rather than relying solely on hard fail states.

Campaigns were also split across multiple ships, each offering distinct bonuses. This directly addressed feedback around game length and gave players more variety and replayability without dramatically increasing scope. These ships will also act as an entry point for future content.

Devlogs, Scope, and Sustainability

Alongside these updates, I produced SENTRY Devlog 3, covering the new content and features added during this period.

As with Something in the Water, producing a devlog so close to a major release meant stepping away from active development. While these videos are valuable, I am increasingly aware that their scope needs to be tightly controlled. Going forward, especially with Major Update 2, the upcoming co-op release, I want to be more deliberate about how and when video production fits into the development cycle.

What I Learned from the DOOM Mapping Jam

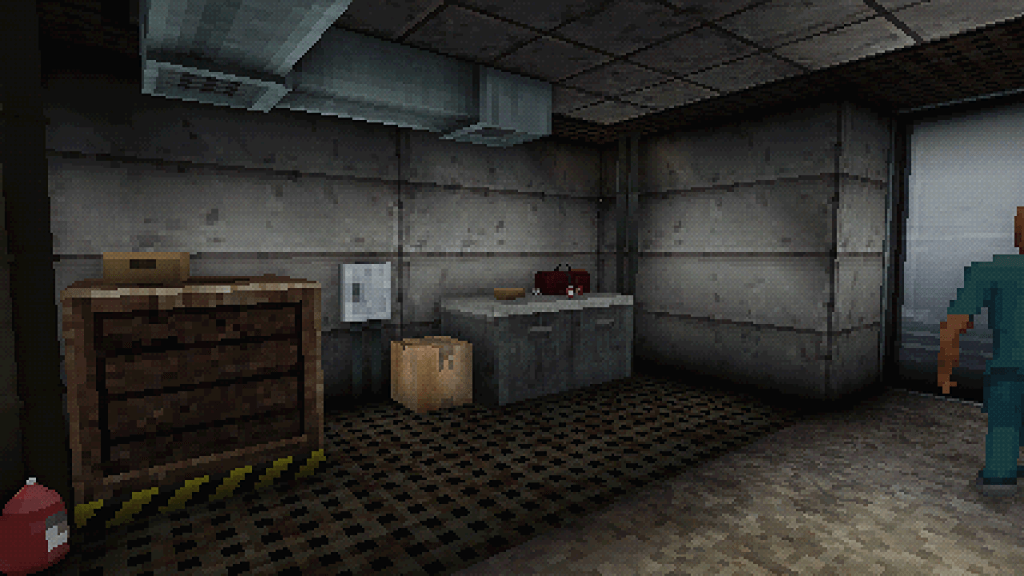

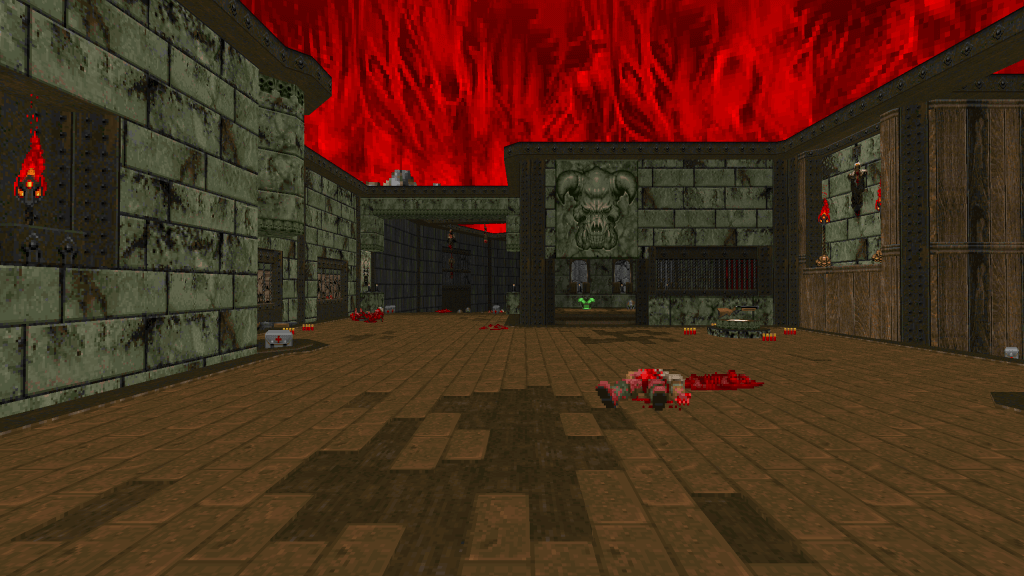

Towards the end of the year I took part in a mapping jam for DOOM. The challenge was to create a multiplayer deathmatch map in just one month. On the surface, this was a small, throwaway side project, but in practice it was one of the most refreshing and educational pieces of work I did all year.

Each constraint was absolute: limited assets, limited mechanics, limited time. Combine that with my unfamiliarity with the tools, and this forced every decision to matter. Layout, flow, sightlines, and player psychology (i.e. pure level design) had to do the heavy lifting. I decided to take an old level I’d created for a cancelled Xbox 360 iteration of Ryse and adapt it for DOOM.

What surprised me was how transferable the lessons were between games. Working within DOOM’s strict limitations tested my instincts around readability and spatial clarity. These are skills that can dull when working in modern engines with endless flexibility and perhaps less direct oversight on visuals due to split disciplines. It was good flex those muscles again.

The map itself is modest, but the process was instructive in a way that larger projects often aren’t. It was a reminder that small, focused creative exercises (like game or mapping jams) can be more clarifying than sprawling long-term projects.

Overall, it went super well and opened my eyes to the possibility of future work in the DOOM engine. I do have ideas for where I could take this further, but it’s also worth noting areas where I feel I could improve. For example, my lack of familiarity with DOOM II’s texture set resulted in some confusion around the elevators. In the video, I mention some creative solutions (such as using SIGIL’s teleporter language), however the quickest and easiest starting point would be to use move conventional textures. Sometimes you don’t need to reinvent the wheel!

Key Takeaways from 2024

Looking back, a few clear lessons stand out:

- Video production significantly impacts development momentum and needs to be treated as a large commitment, not a side task

- Early Access is as much about managing expectations as it is about iteration

- Short creative side work strengthens design thinking and keeps you sharp

- Clarity and restraint matter more than ambition when resources are limited

- …and I should probably be more experimental in 2025!

These aren’t new lessons, but 2024 forced me to confront them directly.

Closing Thoughts

So looking back on the year has clarified where I invest my creative energy. I’m still trying to find the sweet spot between my main project, (SENTRY), my free-time project, (Something in the Water), and where I get to flex my creative musicles (such as the DOOM map). While the DOOM map was fun and satisfying, it had limited reach and doesn’t fully align with where I feel I’m headed. I do have ideas for future DOOM work, however shortly after the jam I made the decision to broaden my options and be more intentional about what I focus on next!

So What’s Next?

In September, I started working as a level designer on REDACTED with REDACTED. I’ve been on the project for a couple of months now, and I’ve been having a blast. My skillset complements the team well, and the style of game is essentially in the same ballpark as something I’d make myself. I can’t wait to talk about this more in the coming year!

Going into 2025, my focus is on simplifying; fewer concurrent commitments, clearer goals, and more deliberate use of my time. That doesn’t mean abandoning documentation or side projects, but it does mean being honest about the trade-offs they introduce… That’s going to be tough!

If there’s a single theme to carry forward, it’s this: depth beats breadth. I’d rather make slower, more coherent progress on fewer things than continue splitting my attention across too many fronts.

And finally, thanks to everyone who has stuck around, read the blog, watched the videos, or shared any of my work. It really means a lot. Here’s to an awesome year of game development in 2025!