A level design case study documenting blockout workflows, playtest iteration, and spatial problem-solving during early game development. This is written for designers interested in how layout, pacing, and player behaviour are shaped when mechanics and metrics are still evolving.

Case Study: Cairo

This post documents my level design process on Cairo, the first map for Last Round – a competitive, last-man-standing multiplayer game set during the golden age of spycraft.

Cairo reflects how I approach blockouts, iteration, and responding to playtest feedback when mechanics and metrics are still evolving. Last Round is an early-stage project and has never been publicly released; this case study focuses on my level design process and the lessons learned rather than a finished product.

About Last Round

Last Round is a multiplayer game where players assume the roles of special agents operating across a range of espionage-themed locations.

Each match begins with every player armed with a pistol containing a single bullet. A bullet is earned for every kill. If all bullets are spent and players remain alive, a single bullet spawns at a random location, visible to everyone, resulting in a mad dash to the bullet’s location.

At the time of writing, this is the core mode of play. Even in its early state, it proved to be tense, readable, and really rather fun. The project is being developed by Joe Wintergreen, Benjamin Blåholtz, among others, with my contribution focused on level design.

Cairo – Layout Overview

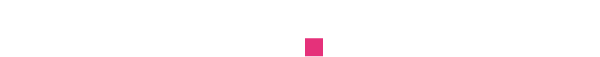

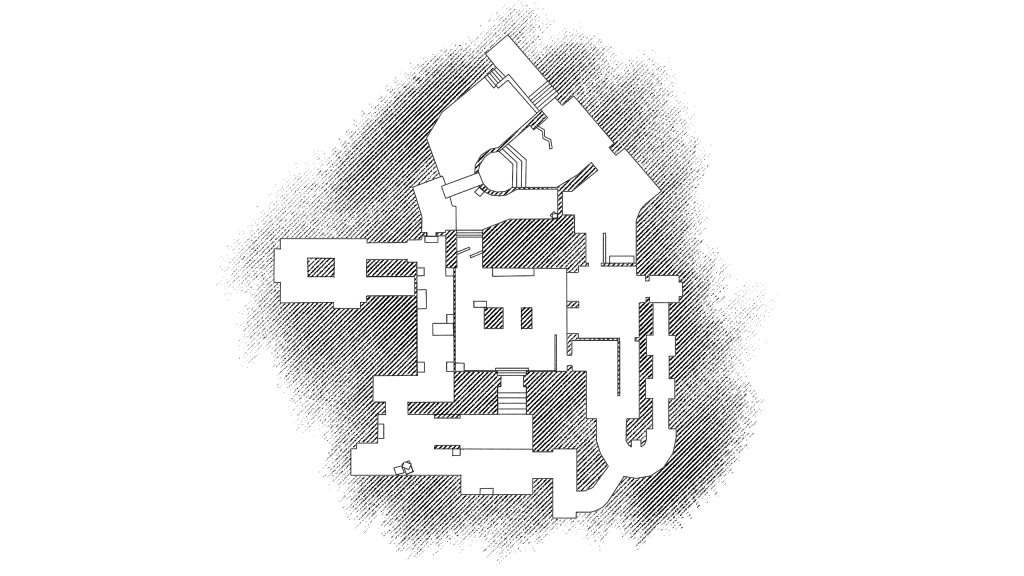

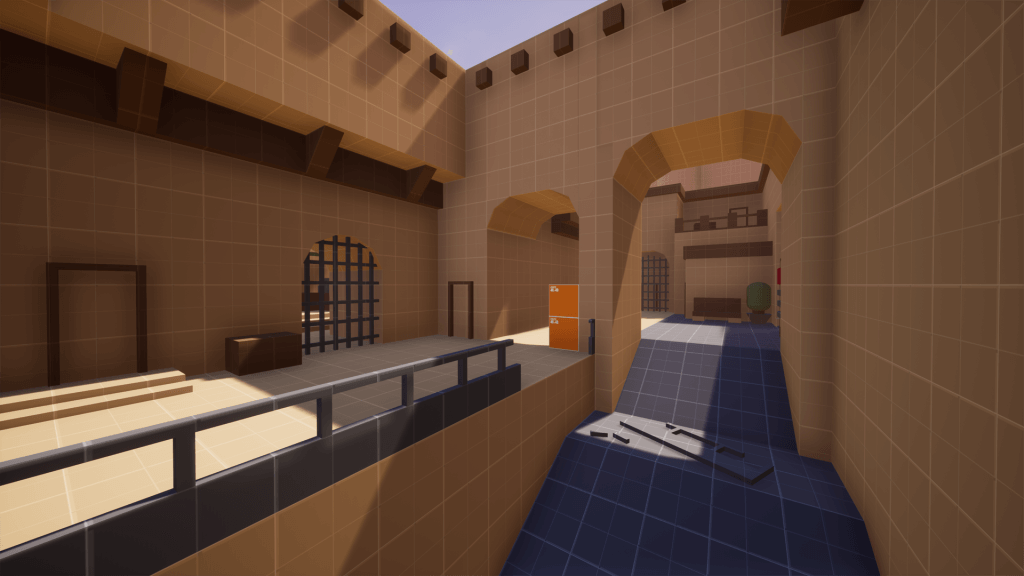

Cairo is a compact map built around a series of overlapping loops connecting two adjacent arenas. Players move through large function rooms, open market squares, and tight, winding side streets.

The layout was designed to:

- Support constant movement – reduce safe holding positions and encourage players to keep repositioning

- Prevent dominant sightlines – break up long lines of fire so no single angle or position controls large portions of the map

- Encourage risky engagements – create short, readable encounters where hesitation carries a cost (i.e. hiding spots)

Before showing the finished blockout, it is worth outlining the thinking behind the layout and how it evolved.

First Steps – Setting and Intent

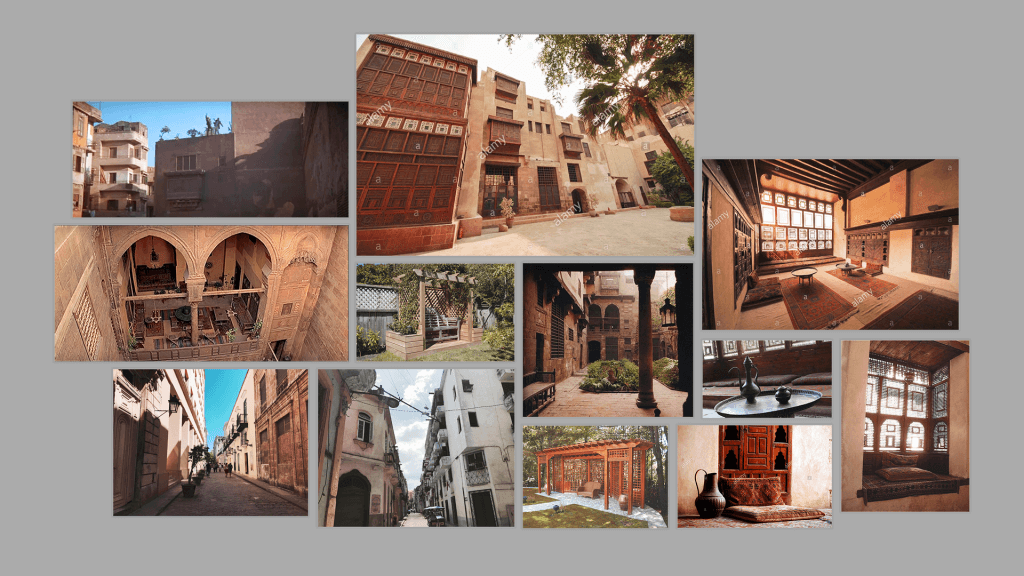

When I joined the project, the team had already discussed Cairo as the first map. The choice was one of readability.

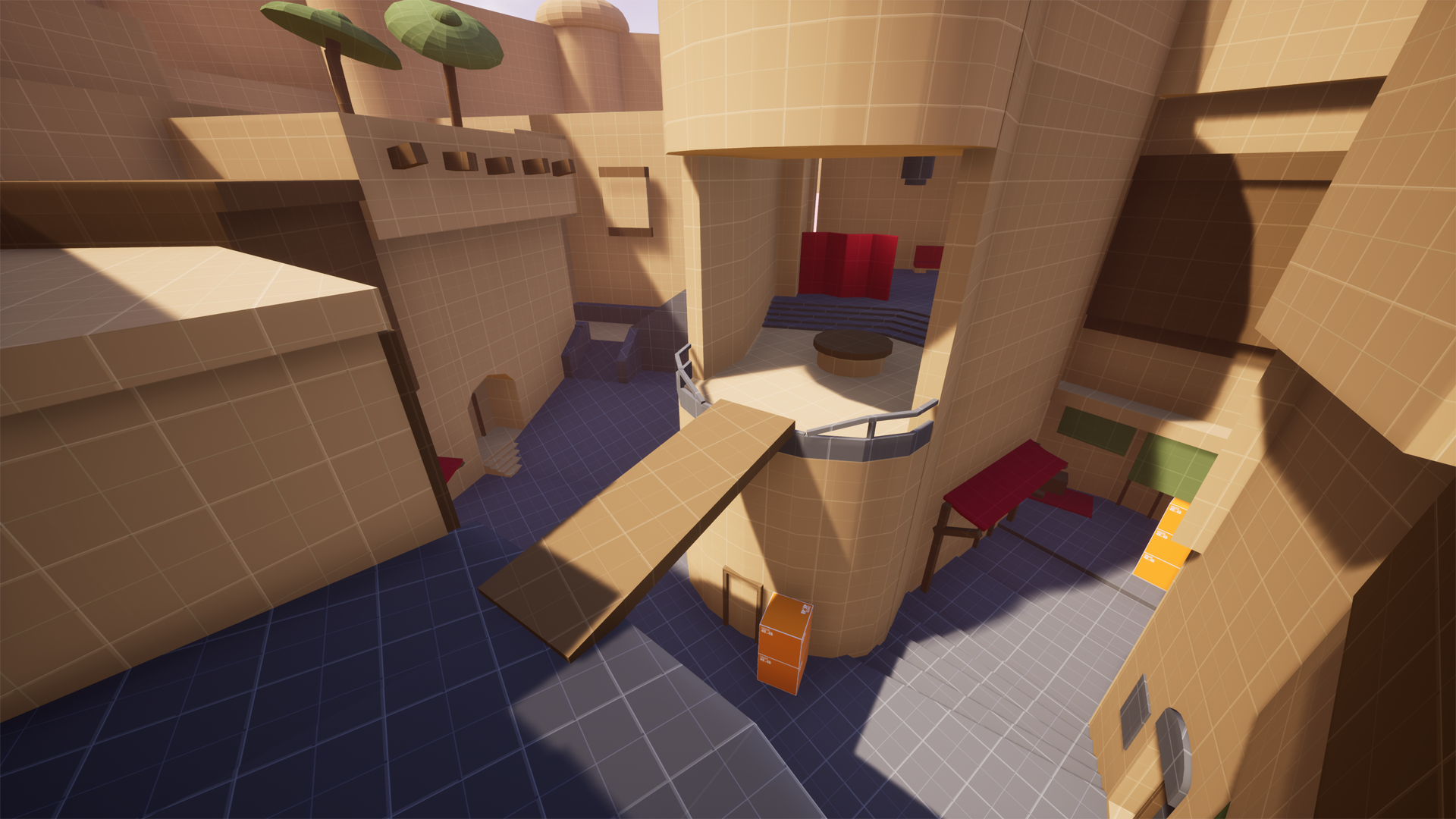

Cairo offers:

- Interiors open to blue skies

- Warm, sandy colour palettes

- Large, bold architectural shapes

These qualities provide strong contrast against the darker player characters and their lanky silhouettes – an important consideration in a fast, lethal multiplayer game.

With the setting agreed, the next step was gathering reference to ground the blockout and align expectations. Much of this reference came directly from artists who would later work on the map. Getting art direction and design intent aligned early avoids costly misunderstandings later.

Pro tip: aligning art direction and design intent before heavy production begins is one of the most effective ways to keep a level cohesive (and the key to true level design happiness)!

Building the Blockout

Level design is an iterative process, especially when mechanics, player speed, and engagement ranges are still being defined. In these conditions, flexibility matters more than fidelity. This is where the blockout comes in.

For the uninitiated, a blockout (sometimes referred to as greybox, blockmesh, whitebox, etc.) uses simple geometry to prototype a layout before visual detail is applied.

I approach blockouts using bold, simple shapes to ensure nothing feels precious. If something needs to change, it should be painless to do so. This approach is consistent with how I typically handle blockouts.

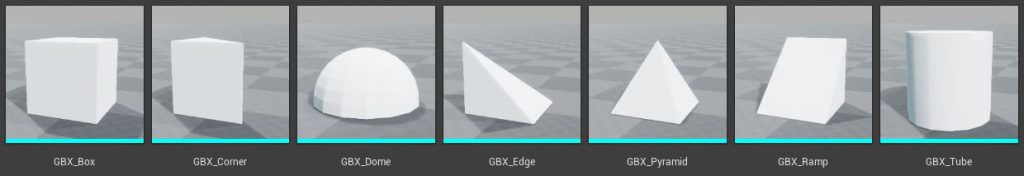

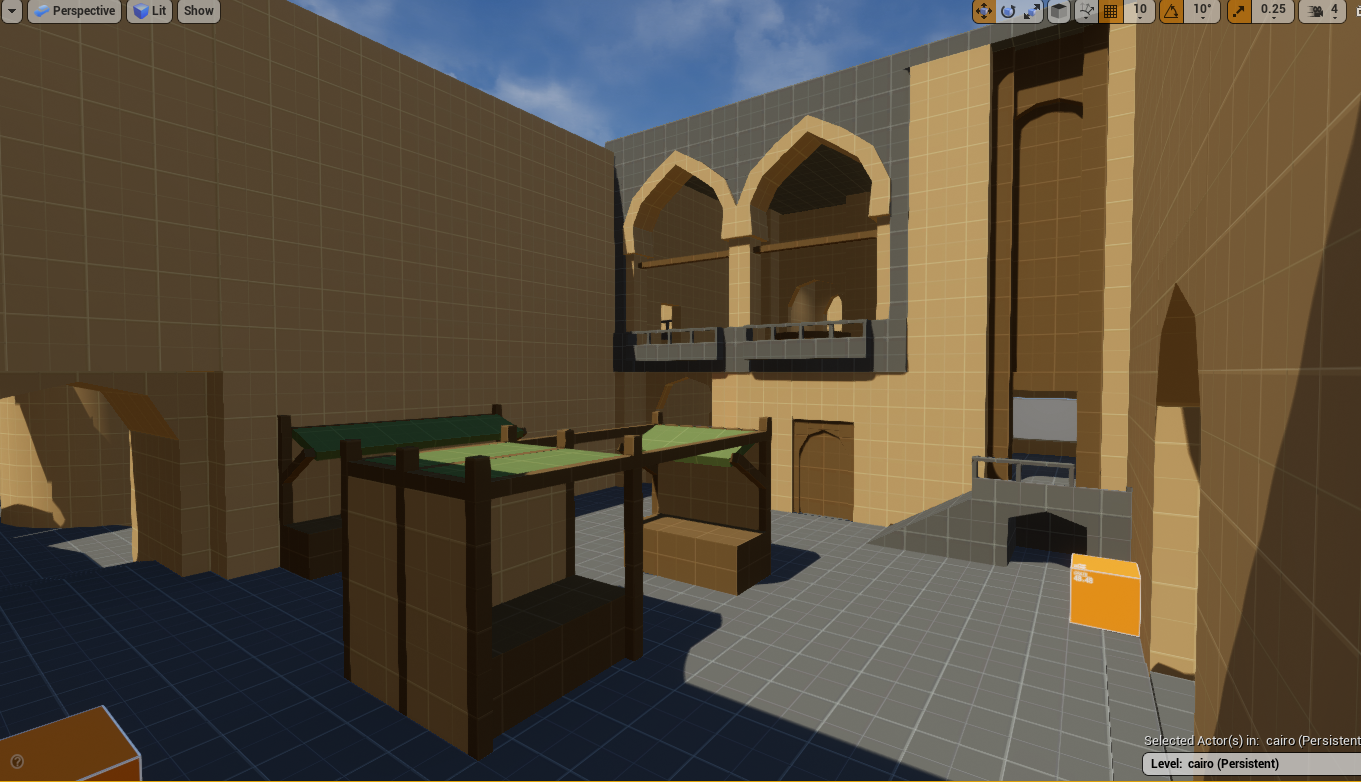

For Cairo, I blocked out the level in Unreal using scaled primitives. The project used multiples of 10 rather than power-of-two grid sizing, so I created a custom set of blockout meshes in Blender to match those constraints.

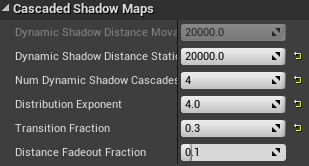

One drawback of scaled primitives is that lightmap UVs scale along with the geometry, which can cause lighting artefacts when using baked lighting. At this stage, I mitigated the issue by increasing Cascaded Shadow Map values on the directional light. This is not ideal for performance, but during an art-free blockout phase it was an acceptable trade-off.

Design Intent, Metrics and Playtesting

The blockout forms the foundation of the level. Once complete, it needs to be tested aggressively.

If the blockout is solid, responding to playtest feedback should be trivial – and to be honest, expected.

In multiplayer levels, my attention is usually focused on:

- Sightlines – lines of player visibility across the level

- Engagement distances – typical player encounter ranges

- Time between encounters – the time in seconds from spawns/objective locations

- Cover patterns – the distribution and flow of physical blockers

Essentially, my goal is to control engagement. Sightlines are shaped to prevent dominance from extreme angles, while space is used deliberately to vary combat between tighter and wider encounters (without pushing either to an extreme). Spawns, objectives, and cover configurations are also distributed to balance pacing, guide flow, and create contrast in player protection and traversal.

Cairo was no exception.

Responding to Feedback

When a game is early in development, it can be a challenge to define metrics and/or make judgement calls on engagement ranges. Playtesting is an essential remedy to this uncertainty and helps developers to get a feel for the game they’re making.

Early playtests surfaced several issues:

- Sightlines were often too long

- Certain areas saw little or no action

- Players frequently snagged on collision

- Long-range “pie-slicing” slowed the pace and created frustration

Pie-slicing is a tactical movement technique where players slowly clear angles one at a time, often resulting in cautious, slower pacing. This is effectively the video game equivalent of “checking corners”.

Layout Adjustments

Based on this feedback, I revisited the blockout with a focus on tightening engagement ranges and improving flow. Every angle and line of sight was reviewed, with geometry adjusted to encourage faster, more decisive encounters.

An important part of level design is knowing when to preserve intent and when to pivot. Layouts should evolve in response to playtests, not resist them. The same applies to visuals.

Visual Exploration

Throughout the blockout phase, I kept visual detail intentionally light. The goal was to communicate spatial intent rather than aesthetics.

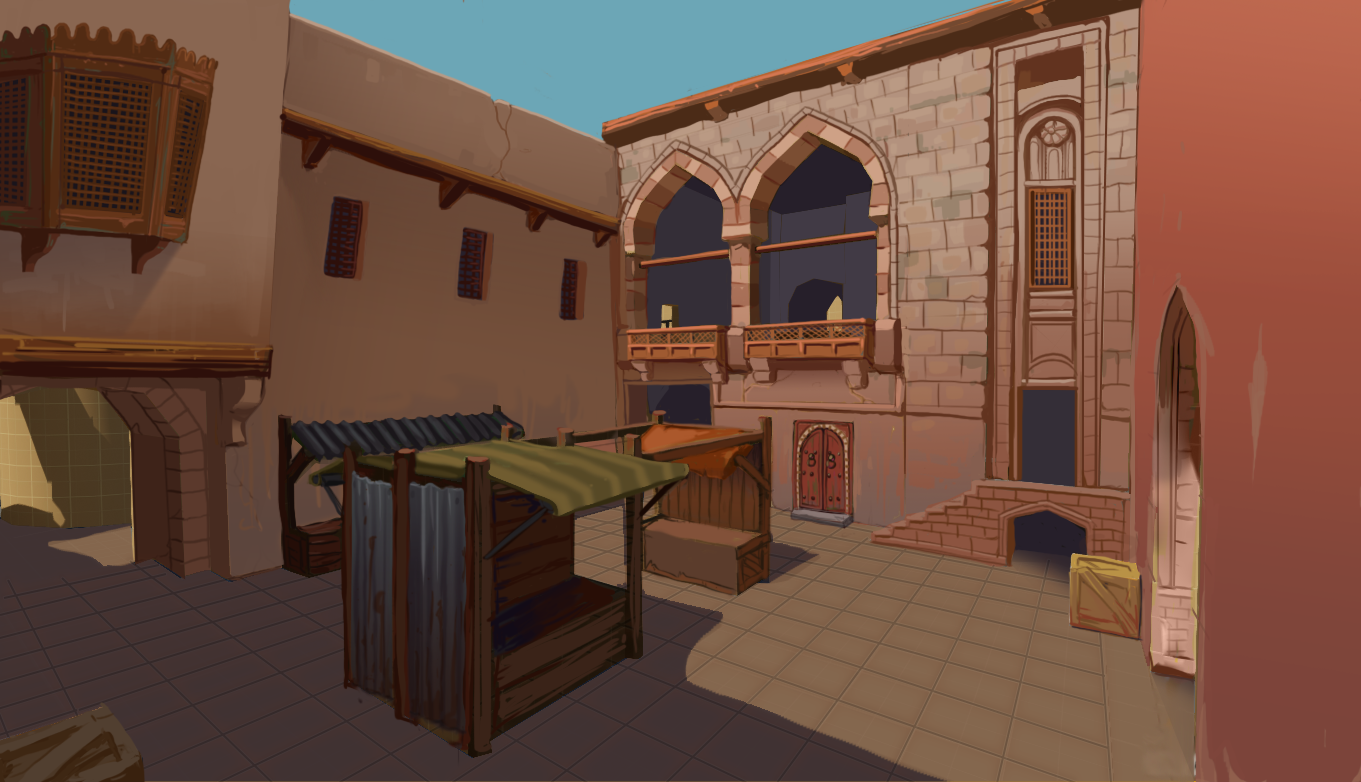

Using reference material, I added just enough detail to suggest how spaces should feel and function. This helps artists understand the purpose of each area and provides a starting point for prop placement and environmental storytelling.

Paintovers provided by the art team were particularly useful. They allowed artists to explore ideas quickly while giving me feedback I could fold back into the layout. This back-and-forth helped ensure the level’s visual identity supported its gameplay goals.

I can’t wait to see what the finished version of Cairo looks like once the artists get ahold of it.

Closing Thoughts

Working on Cairo – and Last Round more broadly – has been a rewarding experience. The project offered a low-pressure creative outlet, allowing me to focus on a single aspect of development and iterate at a considered pace.

The short video below shows the Cairo layout during this phase of development, before any visual polish.

While Last Round was still finding its feet in areas such as pacing and optimal player count, the core experience was already strong. I was very much looking forward to the next round of playtests.

Key Takeaways

If you’re stopping by and skimming for practical lessons, here are the core takeaways:

- Strong blockouts prioritise flexibility over detail

- Aligning art direction and design intent early saves time later

- Multiplayer pacing lives and dies by sightlines and engagement distance

- Playtest feedback should challenge layouts, not just polish them

- Early visual exploration benefits both designers and artists